Excellent and critical question that touches upon geopolitics, internet governance, and technological infrastructure. Let’s break it down systematically.

The Core Reality, Does India, 100%, Depend on the USA, for Internet Service,

1. The Core Reality, Does India, 100%, Depend on the USA, for Internet Service,

The short answer is no, India does not 100% depend on the USA. However, the relationship is one of asymmetric dependence, where the US holds a disproportionate influence over critical components. The dependence is not on “internet service” in the broadband provider sense, but on the underlying architecture and governance.

keep learning more from similar articles

Key Areas of Dependence/Influence:

· Root Servers & Domain Name System (DNS): The ultimate “phonebook” of the internet is controlled by 13 root server clusters. While they are geographically distributed, a significant number (10 out of 13 organizations managing them) are based in the United States and subject to US jurisdiction. ICANN, the global coordinator for the DNS, is a non-profit but was historically under US Department of Commerce contract, and US law can still exert pressure.

· Submarine Cable Landings: Most of India’s international internet traffic flows through submarine cables. While these are consortia of global companies, a large number of these cables land in or are financed by US companies (like Google, Meta, Amazon) or have US entities as major partners. A US government order could, in theory, compel these companies to throttle or reroute traffic at the cable landing stations.

· Technology & Platform Giants: The global internet ecosystem is dominated by US-based companies: Google (Search, Android, Cloud), Meta (Social), Amazon (Cloud, AWS), Microsoft (OS, Cloud, LinkedIn), Cisco (routers), Apple, etc. An internet “blackout” could mean these platforms being made inaccessible from India, which would cripple business, communication, and services.

· Cloud Infrastructure: A vast portion of Indian government and corporate data resides on servers owned by Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. A US-directed blackout could theoretically lock India out of its own data hosted on these platforms.

2. India’s Alternatives and Mitigation Strategies

India is not a passive player and has been developing strategic alternatives, though they are works in progress.

· Physical Infrastructure Diversification:

· New Cable Routes: India is actively promoting cables that bypass potential choke points. Examples include the India-Europe connectivity via the Middle East (IMEC corridor – though delayed) and cables connecting directly to Southeast Asia (like with Singapore).

· “Digital Public Infrastructure” (DPI): India has built sovereign stacks like UPI (payments), Aadhaar (identity), and DigiLocker (documents). In a scenario where US platforms are cut off, these core citizen-service layers would continue to function domestically. This is a form of application-layer sovereignty.

· BharatNet: The project to connect all villages with broadband is a domestic physical network project, insulating the last mile from international issues.

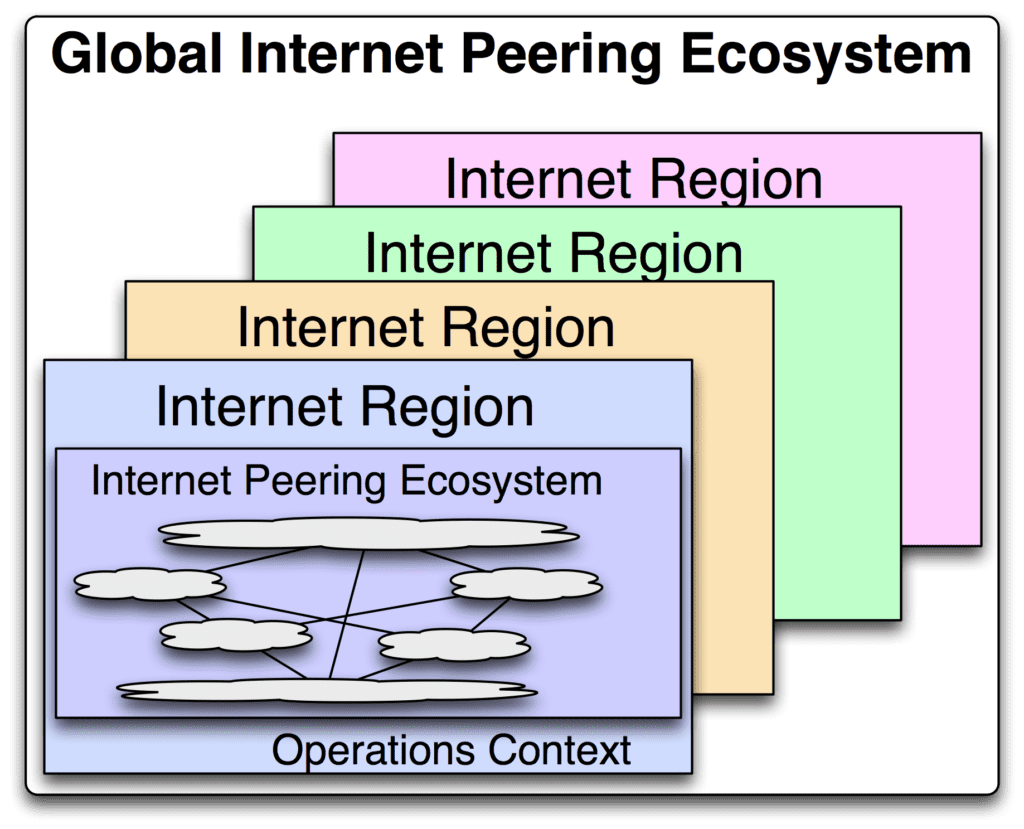

The Global Internet Ecosyatem .

· Governance & Diplomatic Leverage:

· Multi-Stakeholder Model Advocacy: India actively participates in global internet governance forums like ICANN and the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), arguing for a truly multi-stakeholder model to prevent any single country’s dominance.

· Data Localization Policies: Regulations like the Digital Personal Data Protection Act mandate certain data be stored within India. This is a direct move to gain control over data, even if the cloud service provider is American.

· Pushing for “Digital South” Leadership: India positions itself as a leader of the Global South, advocating for a more equitable digital order, which indirectly counters US hegemony.

· Developing Indigenous Tech Stack:

· INDIAai, MeitY Startup Hub: Promoting homegrown AI and tech solutions.

· RISC-V and Semiconductor Missions: Long-term plans to reduce dependence on core chip architectures dominated by US-designed ARM/x86.

· Government RuNet Test: In 2021, India tested a scenario of disconnecting from the global internet to check the resilience of its National Internet Exchange of India (NIXI) and domestic networks. This shows preparedness for a “splinternet” scenario.

3. The Critical Difference: Why Isn’t India Like China?

This is the heart of the matter. China’s near-total internet sovereignty was a deliberate, two-decade-long, authoritarian strategic project. India’s path is fundamentally different due to:

· Timing of Internet Adoption: China connected to the global internet in 1994 when it was still nascent. The CCP saw it as a strategic threat and immediately began building parallel systems (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) behind the Great Firewall. India embraced the open, global internet in the mid-1990s during its economic liberalization, allowing US giants to flourish organically.

· Political System & Ideology: The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) primary objective is control and regime survival. A controlled, censored intranet (often called the “Splinternet”) is a feature, not a bug. India is a democracy with a strong tradition of free speech and open markets. Building a Great Firewall would be politically unacceptable and legally challenged.

· Economic Model: China followed a state-capitalist, protectionist model, actively banning foreign competitors to nurture domestic champions. India, until recently, followed a more open-market model, where the best global products (Google, Facebook) won because local alternatives didn’t match up. This created deep market entanglement.

· Technological Capacity in the 1990s-2000s: When the internet boomed, China had a strong, state-directed engineering base to reverse-engineer and build alternatives. India’s strength was in IT services, not product innovation for the mass consumer market. It became the back office for the world, not its product lab.

· Scale of Domestic Market: China’s 1.4 billion population with a unified language and culture provided a massive, captive market to sustain its parallel internet ecosystem from day one. India’s market, while large, is fragmented by language, literacy, and income, making it harder for a single indigenous player to achieve the scale needed to compete with global giants quickly.

Conclusion

· A complete US “blackout” of India is a low-probability, high-impact scenario (akin to a digital act of war). It is unlikely due to massive mutual economic destruction and geopolitical repercussions.

· India is not 100% dependent, but is critically intertwined with the US-dominated global internet ecosystem at the infrastructural and platform layers.

· Unlike China, India’s dependence was a choice born of its democratic ethos, open markets, and late-mover disadvantage in the product space. It traded sovereignty for rapid integration into the global digital economy.

· India is now actively working to re-balance this dependence through infrastructure diversification, data laws, and promoting indigenous stacks, but it seeks strategic autonomy, not isolation. It aims to be a “swing state” in the digital world, capable of engaging with all blocs without being wholly dependent on any one.

In essence, China chose digital sovereignty from the start, at the cost of global integration. India chose global integration and is now, in the age of tech wars, trying to retroactively build elements of sovereignty without sacrificing its open character.