· The Gallbladder: Your Tiny, Mighty Digestive Organ Explained

· Slug: gallbladder-function-removal-disorders

· Meta Description: What does your gallbladder do? Learn about bile, gallstones, why surgery is needed, life after removal, and metabolic impacts. Your complete guide to gallbladder health.

· Focus Keyphrase: Gallbladder function (ICMR Guidelines on gall ballader read more on external ICMR link)

· Synonyms: Gallstones, cholecystectomy, bile, digestive system, gallbladder removal

The Gallbladder: Your Tiny, Mighty Digestive Organ Explained

Have you ever wondered about the small organ tucked under your liver? Your gallbladder plays a key role in digestion. But what happens when it causes trouble? This blog explains everything. We will explore its anatomy, function, and what occurs when it is removed.

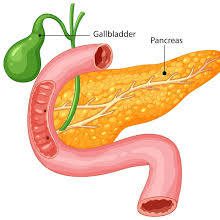

Alt Text Gall bladder

What is the Gallbladder? Definition and Anatomy

The gallbladder is a small, pear-shaped organ. It sits just beneath your liver on the right side of your abdomen.

Think of it as a storage sac. It is structurally attached to the liver via tiny tubes called bile ducts. This connection is crucial for its primary job: managing bile.

The Metabolic Function of the Gallbladder and Bile

The gallbladder itself does not produce bile. The liver creates bile, a greenish-yellow fluid vital for digestion.

The gallbladder’s main metabolic functions are:

· Storage: It stores and concentrates bile between meals.

· Release: It contracts to release a powerful shot of bile when you eat fatty foods.

Bile is essential for digesting fats. It breaks down large fat globules into tiny droplets. This allows enzymes from the pancreas to digest them effectively. Without bile, your body would struggle to absorb fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K.

The Journey of Bile: Secretion to Storage

1. Secretion: Your liver constantly produces bile.

2. Diversion: When you are not eating, a valve closes the main duct to the intestine. Bile is diverted into the gallbladder.

3. Concentration: The gallbladder absorbs water from the bile, making it more potent and concentrated.

4. Release: You eat a meal, especially one containing fat. Hormones signal the gallbladder to contract. It squeezes the concentrated bile into the small intestine to aid digestion.

How Does Liquid Cholesterol Become a Gallstone?

This process is at the heart of most gallbladder problems. Bile contains cholesterol, bile salts, and bilirubin (a waste product).

Under normal conditions, these components are in balance. But sometimes, the liver excretes too much cholesterol. The bile becomes oversaturated—it cannot hold all the cholesterol dissolved.

This excess cholesterol starts to crystallize. These tiny crystals act as seeds. Over time, they clump together and grow, forming solid stones. This is similar to adding too much sugar to tea; eventually, it will not dissolve and forms crystals at the bottom.

Why Don’t These Stones Dissolve?

Once formed, gallstones are notoriously stubborn. The very environment that created them—an imbalance in bile composition—prevents them from dissolving.

The bile becomes unable to re-dissolve the hardened cholesterol or bilirubin. The stones can range from the size of a grain of sand to a golf ball.

Why Do Doctors Decide to Remove the Gallbladder?

Doctors do not remove the gallbladder lightly. The decision for surgery, a cholecystectomy, is common. It is typically for one reason: symptomatic gallstones.

This includes:

· Biliary Colic: Intense, cramping pain in the upper right abdomen after eating.

· Cholecystitis: Inflammation of the gallbladder, often from a stone blocking its outlet. This is a medical emergency.

· Pancreatitis: Gallstones can block the pancreatic duct, causing life-threatening pancreas inflammation.

· Choledocholithiasis: Stones that escape into the main bile duct, causing blockage, jaundice, and infection.

The gallbladder is an organ you can live without. Removing it is a cure for the pain and dangerous complications of gallstones.

Life After Removal: Where Does the Bile Go?

After your gallbladder is removed, your liver does not stop producing bile. It simply has no storage tank.

Bile trickles continuously from the liver directly into the small intestine. Without a gallbladder to concentrate it, the bile is thinner and flows constantly rather than in a powerful squirt when needed.

How Come Stool is Yellow-Brown? The Role of Bile

The characteristic brown color of your stool comes from bile. As bile travels through your intestines, gut bacteria break down its main pigment, bilirubin. This chemical process turns it from greenish-yellow to brown. Without enough bile, stools can become pale, grey, or clay-colored.

Is Bile Acidic? A Comparison with HCL

This is a common point of confusion.

· What is HCL? Hydrochloric Acid (HCL) is the extremely strong acid produced by your stomach. Its pH is very low, around 1.5 to 3.5.

· Is Bile Acidic? No. Bile is actually alkaline (basic). Its pH is around 7 to 8. This is crucial. One of its jobs is to neutralize the acidic stomach chyme (partially digested food) as it enters the small intestine. This creates an optimal environment for pancreatic enzymes to work.

Post-Surgery Symptoms: Why the Discomfort?

It is common to experience digestive issues after gallbladder surgery. This is often called Postcholecystectomy Syndrome.

· Why does the abdomen get enlarged? This is often temporary bloating from the gas used to inflate the abdomen during laparoscopic surgery. It usually resolves within a week.

· Constipation, Diarrhea, and Dysentery: The continuous drip of bile can be irritating to the colon. It can have a laxative effect, leading to diarrhea, especially after fatty meals. Conversely, some pain medications after surgery can cause constipation. The system is adjusting to a new bile delivery method.

Why is Bile Greenish in Color?

The green color of bile comes from biliverdin, a green pigment formed when old red blood cells are broken down. Biliverdin is then converted into the yellow pigment bilirubin. The mix of these pigments gives bile its distinctive greenish-yellow hue.

Significant Metabolic Functions and Disorders After Removal

Your digestive system can adapt well to life without a gallbladder. However, some significant changes and potential disorders can occur:

1. Impaired Fat Digestion: Without a concentrated burst of bile, digesting large, fatty meals becomes difficult. This can lead to:

· Fat Malabsorption: Undigested fat passes through the gut.

· Fat-Soluble Vitamin Deficiency: Poor absorption of Vitamins A, D, E, and K.

· Gas, Bloating, and Diarrhea: Undigested fat can cause these symptoms.

2. Bile Acid Diarrhea: The constant flow of bile acids into the colon can irritate the lining, drawing water into the colon and causing chronic diarrhea.

3. Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction: In some individuals, the valve that controls bile and pancreatic juice flow can spasm after surgery, causing severe pain.

Managing Life Without a Gallbladder

Most people live perfectly normal lives. Dietary adjustments are key:

· Eat smaller, more frequent meals.

· Gradually reintroduce healthy fats.

· Limit very high-fat and greasy foods.

· Increase soluble fiber intake to help bind bile acids.

Disclaimer Note

This blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The information provided is not a substitute for professional medical diagnosis, advice, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of your qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

References and Citations

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). (2023). Gallstones. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/gallstones

2. Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Cholecystectomy. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/cholecystectomy

3. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024). Bile. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/bile

4. Behar, J. (2013). Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Biliary Tract: The Gallbladder and Sphincter of Oddi. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Internal link for more reading on health awareness blog visit https://dailydrdose.com